How Alcoholic Drinks have helped us Celebrate the Sun for Millennia

June 19, 2020

Special drinks have always had a role to play in the greatest celebrations. Join us as we trace the history of alcoholic drinks as a feature of seasonal festivities, from the Inca Empire and Midsummer in Ancient England to Wimbledon and Glasto today.

What is the meaning of Midsummer Day?

Midsummer is a celebration of the longest day of the year, when the Earth’s tilt on its axis begins to move the northern hemisphere further from the Sun.

In Northern Europe, Midsummer is traditionally celebrated on a day between June 21 and 25, and on the day before. This may or may not coincide with the summer solstice, which takes place on June 20, 21, 22, and is truly the longest day of the year.

In Scandinavia, Finland and the Baltics, Midsummer remains the second-biggest annual celebration after Christmas. Traditional Midsummer celebrations have largely died out in England, due to the opposition of the Church from the late 14th century up until the Reformation.

Midsummer celebrations have taken lots of different forms over the centuries and around the world. Common themes have included bonfires, feasting, singing, dancing and – of course – drinking.

The role of drinking in celebrating the seasons

The non-fiction author Richard Cohen unearths some fascinating links between drinking and the solstice in his book, Chasing The Sun.

For one thing, Cohen writes of historic Norwegian court records that tell of witches flying through the air, merry on home-brew, many of them riding black cats, on Midsummer Eve.

And then there’s the tale of an old superstition, documented by the British antiquary Francis Gose:

“Any unmarried woman fasting on Midsummer Eve, and at midnight laying a clean cloth, with bread, cheese and ale, and sitting down as if going to eat, the street door being left open, the person whom she is afterwards to marry will come into the room and drink to her by bowing; and after finishing the glass will leave it on the table, and, making another bow, retire.”

On a less supernatural level, beer-drinking was widespread among Midsummer revellers.

Some pagan Midsummer celebrations live on, notably the Midsummer gathering at Stonehenge, where thousands flock every year (except 2020). In Cornwall, beacon fires are still lit on high hilltops on Midsummer Eve.

But what’s even more remarkable is how elements of these celebrations survived in mainstream culture long after paganism was largely stamped out. In the North of England, communities danced around bonfires on summer solstice until the mid-1800s. Cornish immigrants in South Australia used to do the same on June 24th, the southern hemisphere’s midwinter.

Most Brits no longer celebrate Midsummer in any pagan sense, but there are parallels in how we celebrate the turn of the seasons. From the revelry at Glastonbury Festival around Midsummer, to Wimbledon and the Henley Regatta with their much-cherished Pimm’s cocktails in July, the nation continues to let its hair down around this time of year.

What links Wild Knight distillery to sun worship?

If you’ve ever researched Midsummer and sun worship in Britain, you’ll know that in these subject areas, pretty much all roads lead back to Stonehenge.

It seems that Stonehenge may have acted as a kind of prehistoric calendar, through the alignment of its standing stones with the Sun. Famously, at summer solstice, the Sun rises behind the heel stone of Stonehenge and shines into its very heart. The whole monument is perfectly aligned with both solstices, summer and winter.

One of the theories on the purpose of Stonehenge – and there have been many theories – was that the famous stone circle was built as a tomb for Boadicea, pagan warrior queen of the Iceni. This piqued our interest, as one of our spirits bears her name: Boadicea gin, which we’ve given a bright blue bottle to represent the woad dye the Iceni wore into battle, and bearing a triskelion symbol similar to those used by the tribe.

The Iceni were Celts, and their druidic religion revered the Sun as a supernatural force, along with the moon and the stars. Whether or not Stonehenge was really built as a resting place for Boadicea, it is safe to say the Sun held a special meaning for the great woman and her people. And so, for us, toasting Boadicea with a glass of Boadicea gin this Midsummer will feel like a fitting tribute.

Drinks worthy of special rituals

In some cultures, drinks have been more than just an accompaniment to celebrating the seasons; they’ve been a way worshipping the Sun.

As shown in these incredible photos by Jorge de la Quintana, in traditional Inca ceremonies, chicha, an alcoholic drink made with maize, is sometimes poured into a golden vessel as an offering to the sun god, Inti. It is said that if the liquid disappears, the Sun has truly partaken of the drink – and in some cases, that’s exactly what happens, presumably through evaporation.

Believe it or not, Wild Knight Distillery owes its existence to ritual drinking. Our founders, Steph and Matt Brown, were inspired to set up the distillery after Matt travelled to Mongolia for his brother’s wedding. The wedding day started in traditional Mongolian fashion with the sharing of a bowl of vodka, and the drink played a memorable part in the festivities that followed.

From matrimonial rites in Mongolia to Midsummer in England, special drinks are a constant feature of the greatest celebrations. Whatever you choose to celebrate next, we’d be honoured if you decide to share the occasion with one of our spirits.

Featured collection

All are available with fast delivery throughout the UK mainland. For a gift, add a message during the checkout and we will include a personalised gift note for you.

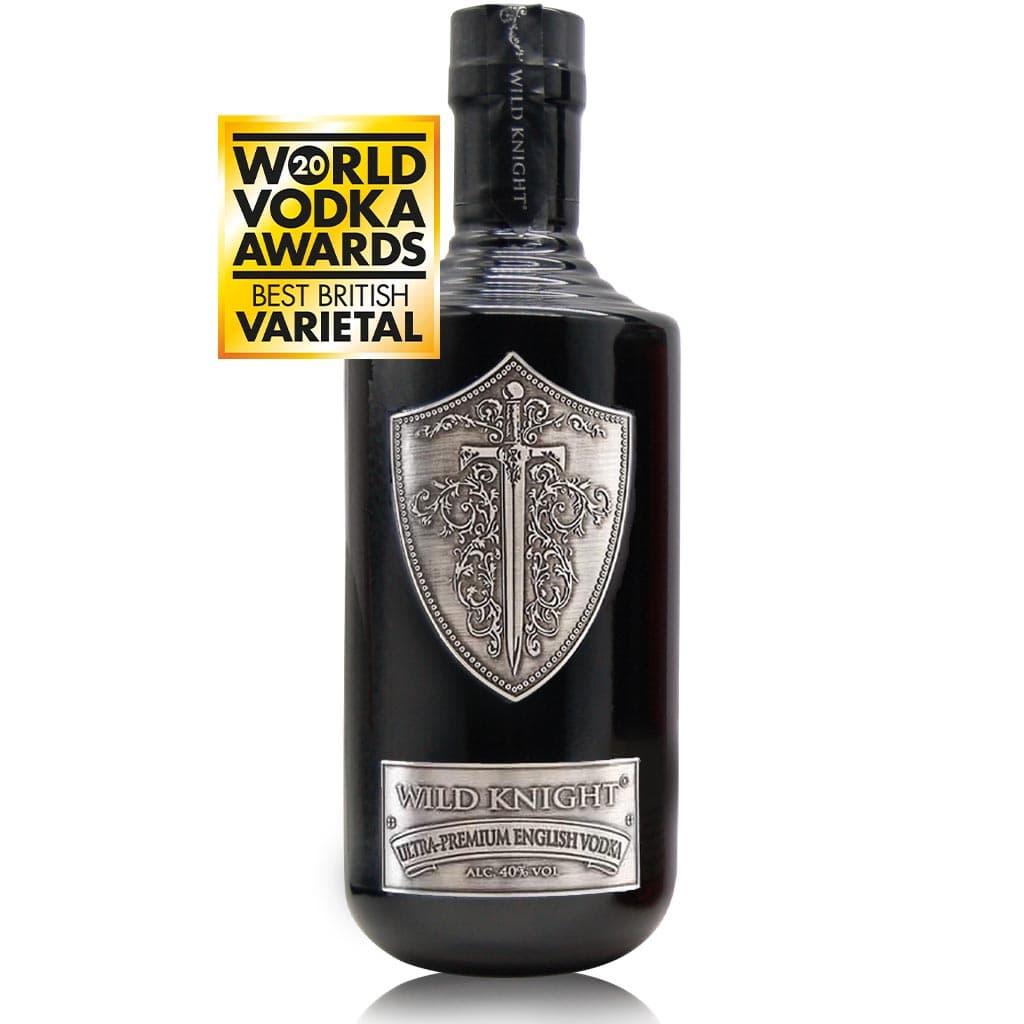

Wild Knight English Vodka is perfect sipped just over ice but there are a wide range of cocktail ideas here for you to try. From classics, to serves for the adventurous.

Nelson's Gold Caramel Vodka is one of our best-selling spirits. Most people will enjoy it neat over ice but we have a selection of suggestions to take Nelson's Gold that one step further.

There is a big world of serves outside of the G&T. Try something new today. We have plenty of ideas for you to taste.

Join Our Community

Get insider access to our latest releases, exclusive offers, and behind-the-scenes updates - delivered straight to your inbox. No spam, just the good stuff.